세계은행이 펴낸 정책보고서 「번영을 위한 이주 : 국제이주와 노동시장」 표지

세계은행이 펴낸 정책보고서 「번영을 위한 이주 : 국제이주와 노동시장」 표지

많은 수의 서류미비 또는 저숙련 이민자 또는 난민이 도착하는 것이 목적지 국가에서 많은 우려를 불러일으키지만, 고숙련 노동자의 고소득 국가로의 이동(때로는 두뇌 유출이라고도 함)은 출신 국가에서 유사한 감정을 불러일으킨다. 이 문제는 기술이 부족한 저소득 국가에서 특히 심각하다.

학문적 연구에 따르면 이주 흐름의 기술 구성은 목적지 또는 출발지 국가의 노동 시장 영향을 결정하는 데 있어 전체 이주자의 수만큼 중요하다. 그러나 고숙련 노동자와 그들의 이주는는 단순한 임금 효과 이상의 의미가 있으며, 이것이 우리가 이 주제에 대해 전체 장(5장)을 할애하는 이유이다.

고숙련 노동자는 오늘날의 세계 경제에서 중심적인 역할을 한다. 그들은 혁신가, 기업가, 과학자, 교사 및 다음 세대의 롤 모델이다. 그들은 복잡한 조직에서 다른 고급 인력의 활동을 이끌고 조정하고 관리한다. 고소득 목적지 국가는 지식 창출의 최전선에 있는 많은 산업을 포함하여 많은 산업을 창출하고 유지하기 위해 외국 인재에 의존한다. 이미 인적 자본 부족을 겪고 있는 저소득 국가는 두뇌 유출이 경제 성장, 공공 재정, 의료 및 교육과 같은 핵심 서비스 제공에 미치는 영향을 두려워한다. 인재의 글로벌 이동성이 세계화의 이점과 그 함정을 얽히게 하는 주요 정책 관심사라는 것은 놀라운 일이 아니다.

시간이 지남에 따라 이주가 점점 더 고도로 숙련되어 호스트 국가와 목적지 국가 모두에 새로운 도전 과제를 제시한다. 포괄적인 데이터를 확보한 첫 해인 1990년에 약 4000만 명의 노동 시장 연령(25세 이상) 이민자가 27개의 고소득 OECD 국가에 거주했다. 초등 교육을 받은 이민자가 전체 인구의 거의 절반을 차지했으며 고등 교육을 받은 이민자가 약 27%를 차지했다. 2010년에 노동 시장 연령의 이주민은 8,500만 명이 넘었고 고등 교육을 받은 이주민은 약 4,300만 명으로 전체의 50%에 가깝다.

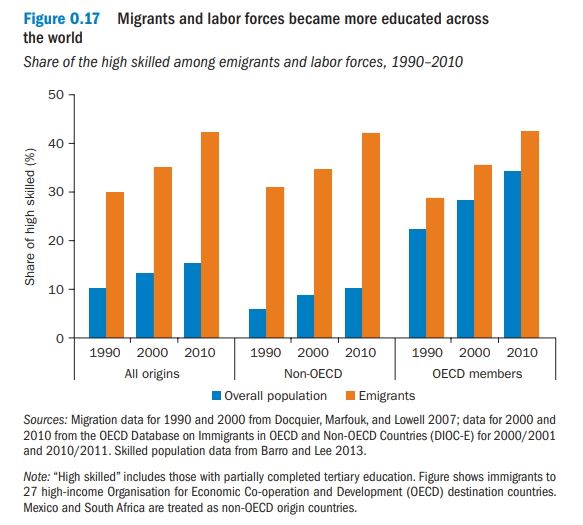

고급 기술 이민의 급격한 증가는 전 세계적으로 고등 교육을 받은 근로자의 공급과 OECD 국가의 수요 증가에 기인한다. 그림 O.17은 1990년 이후 OECD 및 비OECD 국가의 노동력에서 고등교육을 받은 비율(파란색 막대)을 보여준다. 주황색 막대는 같은 지역에서 같은 기간 OECD 국가로 이주한 이민자 중 고등교육을 받은 비율을 나타낸다. 이 그림의 패턴을 관찰한 결과 주목할 만한 게 있다. 첫째, OECD 국가로 이주하는 모든 이민자 중 고등교육을 받은 비율은 매 10년 동안 기본 노동력의 교육 수준의 거의 세 배였다. 고숙련 근로자는 앞서 설명한 것처럼 훨씬 더 이동성이 뛰어나다. 둘째, 고급 기술 이민의 엄청난 증가는 주로 세계적인 고급기술 인구의 증가에 의해 주도된다. 1990년 이후 비OECD 국가에서 고급기술 인력의 비율이 60% 이상 증가했다. 셋째, 고등교육을 받은 개인의 비율이 3~4배 더 높음에도 불구하고 OECD 및 비OECD 출신 국가 모두 유사한 비율(2010년 기준 40% 이상)을 OECD 목적지 국가로 보내고 있다. 그럼에도 불구하고 특히 높은 숙련도 이민 비율을 경험하는 것은 비OECD 국가들이다.

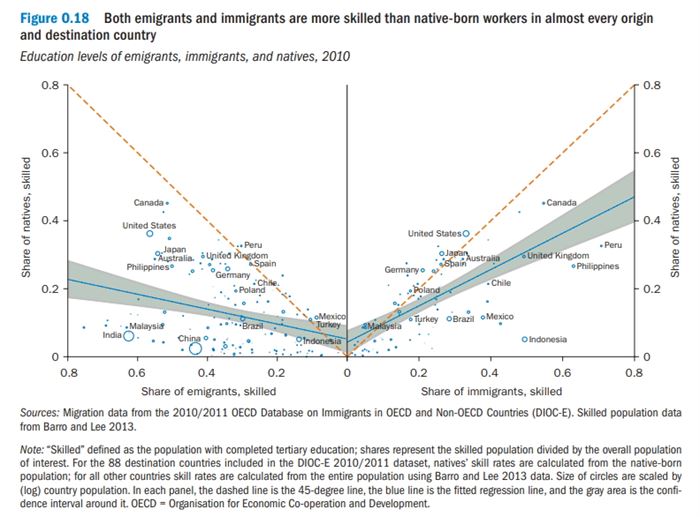

고숙련 이민자 비율의 급격한 증가, 기술 선택은 국가 차원에서도 나타난다. 그림 O.18은 가장 최근 연도인 2010년에 대한 이민자, 이민자 및 원주민 인구 중 고등교육을 받은 사람의 비율을 나타낸다. 왼쪽과 오른쪽 패널의 가로축은 각각 이민자 및 이민자 기술 비율을 나타낸다.

토착민 또는 비 이민자의 교육 수준은 왼쪽과 오른쪽 세로축에 있다. 점선 45도 선 아래의 관찰은 이민자(또는 이민자)가 토착 노동자보다 교육 수준이 더 높음을 의미한다. 보시다시피, 거의 모든 국가가 이 선 아래에 있으며, 이는 국가가 보유하고 있는 것보다 더 많은 교육을 받은 이민자를 보내고 받는다는 것을 의미한다. 소규모 및 저소득 국가는 특히 숙련 노동자의 불균형적인 이주에 노출되어 있다. 미국을 포함한 다수의 고소득 국가의 경우에만 평균 이민자가 평균 원주민 근로자보다 약간 덜 숙련되어 있다. 이러한 국가는 오른쪽 패널의 45도 선 위에 있다.

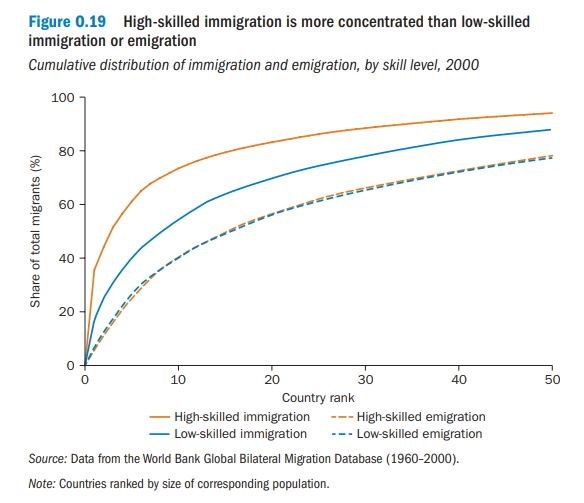

집중도는 소수의 목적지 국가에 집중되어 있는 고숙련 이민자의 경우 더욱 두드러지게 나타난다. 그림 O.19는 기술 수준에 따른 이민자의 누적 분포를 나타낸다. 그래프는 상위 10개 목적지 국가가 전 세계 고급 기술 이민자의 75%를 차지한다는 것을 의미한다. 이 중 4개의 앵글로색슨 목적지(호주, 캐나다, 영국, 미국)는 모든 고급 기술 이민자의 거의 3분의 2의 고향이다. 이러한 집중은 소스 국가에는 존재하지 않는다(고숙련자 이민자의 소스 국가는 다양하다.).

경제적 요인은 이민 및 이민 패턴의 이러한 변화의 많은 부분을 다시 설명한다. 교육 투자 수익이 높고 소득 수준이 높은 국가, 즉 OECD 고소득 국가는 더 숙련된 이민자를 유치한다. 경제가 교육에 대한 보상을 제공함에 따라 이민자 유입의 구성은 숙련도가 더욱 높아짐에 대응한다. 한편, 숙련된 이민자들은 물리적 거리, 언어적 차이, 정책적 장벽을 보다 쉽게 극복할 수 있다.

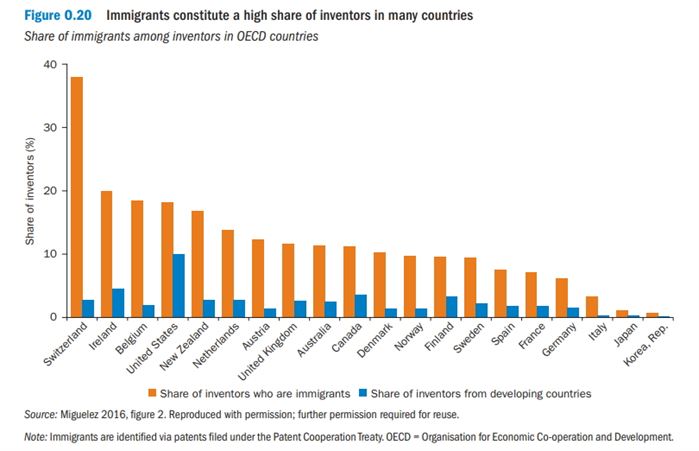

이민자들은 주요 고급 활동에 기여하는 데 있어 엄청난 역할을 한다. 그들은 과학, 기술, 공학, 수학(STEM) 분야에서 그리고 발명가이자 혁신가로 불균형적으로 고용되어 있다. 예를 들어, 이민자들은 특허협력조약에 따라 출원된 국제 특허의 약 10%를 책임지고(차지하고) 있다. 선진국 전체를 살펴보면, 그림 O.20은 발명가 중 이민자의 비율이 거의 모든 국가에서 이민자의 전체 비율보다 훨씬 높다는 것을 보여준다. 또한 개발도상국의 발명가는 특히 캐나다와 미국에서 상대적으로 높은 점유율을 차지한다.

고급 기술 이민 정책

전 세계적으로 국가들은 보다 기술 선택적인 이민 정책을 채택하고 있다. 이 정책은 일반적으로 두 가지 광범위한 체제로 나눌 수 있다. 한편으로 수요 중심 정책은 들어오는 이민자들이 먼저 목적지 국가에서 일자리를 얻도록 요구한다. 따라서 이민자의 거의 즉각적인 고용이 우선시되며 잠재적 고용주와 현재 노동 시장 조건은 이민자의 부문별 및 직업적 구성을 결정하는 데 중요한 역할을 한다. 반면에 공급 중심 정책에서는 들어오는 이민자를 점수 기반 시스템으로 평가해야 한다. 연령, 고등교육, 경력, 직업, 어학능력 등 노동시장의 바람직한 특성을 가진 사람을 우대한다. 이러한 체제에서 이민자들은 일반적으로 실제 구인 없이 고용 허가를 받는다. 여기에는 그들이 도착한 후에 일자리를 찾을 것이라는 가정이 깔려 있다.

공급 중심의 이민 제도의 문제점은 이 개요에서 반복적으로 강조된 바와 같이 어떤 유형의 이민자가 수용국에 가장 큰 혜택을 주는지에 대한 증거가 거의 없다는 것이다. 동기 부여, 창의성, 기업가 정신 및 산업별 지식을 포함한 개인적 특성은 관찰하기 어렵지만 노동 시장에서 이민자의 성공을 결정하는 데 필수적이다. 이민자가 수용국 경제에 기여하는 가장 좋은 지표는 노동 시장에서 제공하는 평가인 일자리 제안이다. 이전 요점을 다시 한 번 반복하자면, 정부는 일반 이민 정책뿐만 아니라 고급기술 이민 정책을 설계할 때 노동 시장의 목소리에 귀를 기울여야 한다. 미국 H-1B, -H-2A 및 H-2B 비자와 같은 수요 또는 고용주 주도 이민 프로그램이 취업 제안 없이 이민을 허용하는 공급 또는 이민자 주도 포인트 시스템보다 선호된다.

이는 다양한 비자 카테고리에 역할이 없다는 의미가 아니라 정부가 취업 허가를 세세하게 관리하거나 어떤 기술이 더 중요한지 추측하려고 해서는 안 된다는 의미이다. 대신 정부 정책은 시장 메커니즘에 더 의존해야 한다. 사용할 수 있는 취업 허가의 수가 제한되어 있는 경우, 바람직한 이민자 특성을 결정하기 어려운 시스템보다 고용주 주도 방식의 유연성이 더 바람직하다. 이것은 숙련도가 높은 이민 계획과 저숙련 이민 계획 모두에 해당된다.

소스 국가에 대한 영향은?

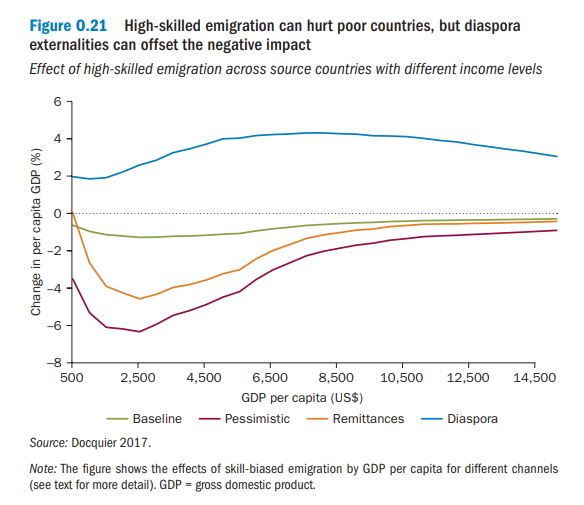

그러나 이 문제의 중요성과 그것이 받는 관심에도 불구하고 고급 기술 이민의 영향에 대한 증거는 결정적이지 않다. 빈곤, 성장 또는 기타 경제 지표에 대한 기술 부족의 영향을 식별하는 경험적 어려움인 데이터 제약은 고급 기술 이민자의 진정한 비용 또는 혜택을 결정하는 데 어려움을 가중시킨다. 한 가지 해결책은 글로벌 이주 데이터베이스를 거시경제 모델과 결합하여 기술 편향된 이주가 가난한 국가에 미치는 영향을 시뮬레이션하는 것이다. 이 실행의 결과는 그림 O.21에 나와 있다.

고급 기술 이민의 영향에 대한 중요한 결정 요인은 고급 기술이 경제 전반에 걸쳐 생성하는 생산성 파급의 정도이다. 그러한 긍정적인 생산성 파급효과가 존재하지 않는다면, 고숙련 이민은 전반적으로 소득 수준에 상대적으로 작은 부정적인 영향(약 1%)을 미친다(그림 O.21의 녹색 선). 그러나 파급효과가 있는 경우, 특히 1인당 소득 수준이 $3,000(빨간색 선) 미만인 원산지 국가의 경우 영향이 매우 심각할 수 있다(거의 6% 감소). 본국으로 송금된 송금액(주황색 선)이 다소 있지만 이 손실을 완전히 보상하지는 못한다.

출신국의 일반적인 대응 중 하나는 이민을 제한하는 것인데, 이는 이민 제한에 대해 몇 가지 중요한 실용적이고 경제적인 반대를 제기한다. 첫째, 모든 증거는 숙련 기술자의 이주를 막는다면 생산성이 떨어질 수 있음을 시사한다. 이민자(고숙련 및 저숙련)는 이민을 통해 막대한 수입을 얻는다. 그들을 생산적으로 만드는 큰 부분은 목적지 국가의 작업 환경이다. 이주로 인한 잠재적인 수입이 없었다면 이 이주자들이 애초에 이러한 기술을 습득했을지 의문이다. 둘째, 현실적으로 이러한 이동제한을 부과하고 시행하는 것은 상당히 어렵다. 목적지 국가가 진입을 막을 수 없는 것처럼 시장의 힘에 직면하여 출발 국가는 출발을 효과적으로 막을 수 없다.

정부가 이민을 방해할 수 없다면 어떻게 해야 할까? 최근 연구는 고숙련 노동자와 아이디어를 위한 세계 시장을 활용하는 최소한 두 가지 유망한 방법을 강조한다. 첫째, 고숙련 이민자의 출신 국가는 디아스포라와 교류하고 외부 효과를 극대화해야 한다. 둘째, 귀국 이주를 장려할 수 있다.

이민자들은 일반적으로 계속해서 사회적으로나 경제적으로 고국에 적극적으로 참여하고 있다. 가장 일반적인 경제적 참여는 송금의 형태를 취하는데, 이는 개발도상국의 많은 가족에게 중요한 수입원이다. 디아스포라 참여 프로그램은 또한 해외 투자자와 기업가를 국내 투자 기회와 연결하고 해외 기술과 지식의 이전을 촉진하려고 시도한다. 유망한 증거는 국가가 고도로 숙련된 디아스포라의 귀환을 성공적으로 장려할 수 있음을 시사한다. 이러한 프로그램의 이면에 있는 아이디어는 사람들이 해외로 이주하여 기술을 습득하는 것이 중요하다는 것이다. 이러한 프로그램은 이민을 방지하기보다는 성공적인 이민자의 귀국을 장려하는 것이다. 그러한 프로그램의 예로는 말레이시아로 돌아온 성공적인 이민자들에게 세금 인센티브를 제공하는 Malaysian Returning Expert Program이 있다. 증거는 프로그램이 성공적임을 시사한다. 그것은 더 많은 귀환 이주를 장려하고 귀국 이주자가 세금을 내기 때문에 대략적으로 비용을 지불한다다(낮은 세율로).

그러한 "두뇌 이득" 효과가 있는 시뮬레이션은 그러한 힘이 숙련된 이민으로 인한 손실을 보상하고 전반적인 경제적 이득으로 이어질 수 있음을 의미한다(그림 O.21의 파란색 선). 그럼에도 불구하고 우리는 고도로 숙련된 이민에 대한 증거, 그 영향 및 그 의미가 이상적이지 않다는 점을 강조할 필요가 있다. 이것은 새로운 데이터와 연구가 절실하고 즉각적으로 필요한 영역 중 하나이다.

International coordination of migration policy 이주 정책의 국제 조정

이 개요에 제시된 정책 권장 사항은 주로 출발지 또는 다른 국가로부터 최소한의 의견을 받거나 조정하면서 대부분의 경우 목적지 국가에서 설계한 일방적 정책으로 설명된다. 권장 사항은 일반적으로 국가별로 독립적으로 시행되는 이주 정책을 반영한다. 그러나 우리는 국제무역, 금융, 안보 등 다양한 분야에서 많은 정책들이 국제협력을 통해 큰 이익을 얻을 수 있다는 것을 알고 있다. 일방적인 정책은 본질적으로 협력과 조정을 통해 내재화할 수 있는 파트너 국가에 대한 외부 효과를 생성한다.

경제적 이주를 규제하기 위한 다자간 프레임워크는 거의 존재하지 않다. 주요 예외는 난민에 관한 매우 제한된 협정이다. EU 또는 동아시아 내의 지역 노동 이동 협정과 같이 지역 수준에서 몇 가지 중요한 예외가 있다. 이러한 다자간 설계의 부재는 국제기관(예: 세계 무역 기구)이 국경 개방, 무역 증가, 통화 정책 조정, 규제 집행 개선에 기여한 국제 무역 아키텍처 또는 금융 협력과 극명한 대조를 이룬다. 이주 정책 분야에서 정부 간의 공식적이고 확립된 협력과 조정의 부재는 많은 비효율, 갈등 및 위기를 초래한다. 우리의 마지막 관찰은 양자적, 지역적 또는 다자적 수준에서 정책 조정이 분명히 필요하다는 것이다.

마지막 생각들

이주의 경제학에 대한 논쟁은 양측이 더 잘 경청해야 한다. 열린 시장의 미덕을 믿는 많은 경제학자들은 노동이 더 자유롭게 움직일 경우 실현될 효율성 향상에 올바르게 초점을 맞추고 있다. 광범위한 추정치에도 불구하고 시장 간 임금 격차에서 알 수 있듯이 특히 이민자들이 실현한 이익은 상당할 것이다. 효율성 향상이 실현됨에 따라 특히 목적지 국가에서 이러한 흐름이 생성할 분배 영향 및 전위를 무시하는 것은 잘못(실수)이다.

이민을 반대하는 사람들에게는 그 반대가 사실이다. 그들의 초점은 이주의 분배적 영향에 있다. 주로 이주자가 일자리를 빼앗고 임금을 낮추는 것이다. 그들은 우리가 보도에 남기고 있는 상당한 효율성 향상(또는 셀 수 없이 많은 100달러 지폐)을 부인하거나 무시한다. 양측 모두 타당한 점을 갖고 있고, 양측은 엉뚱한 곳에서 해법을 찾고 있다.

정책 조치인 솔루션은 파이를 최대한 크게 만드는 동시에 더 균등하게 분배하는 방법을 찾아야 한다. 그러한 재분배 계획에는 목적지 국가뿐만 아니라 원천 국가에서도 노동력의 승자와 패자를 포함해야 한다. 이 과정은 정책 입안자들 사이의 조정과 진보적 사고가 필요하다. 그것이 우리가 경제적 이득을 현실로 전환하는 정치적 메커니즘을 구축할 수 있는 유일한 방법이다. 또한 이러한 문제는 이주에만 국한된 것이 아니라 무역에서 지구 온난화, 금융에 이르기까지 세계화의 다른 모든 측면에 적용된다는 점을 추가해야 한다.

우리는 이러한 진술이 하기 쉽지만 구현하기 어려운 작업이라는 것을 충분히 알고 있다. 우리는 이 연구의 분석과 권고가 이 과정에 기여할 수 있기를 바란다.

High-skilled migration, agglomeration, and brain drain

Although the arrival of large numbers of undocumented or low-skilled immigrants or refugees leads to much concern in destination countries, the exodus of high-skilled workers to high-income countries—sometimes referred to as brain drain—evokes similar emotions in source countries. This problem is especially severe in low-income countries with skill shortages.

Academic research has demonstrated that the skill composition of migration flows is as important as the overall number of migrants in determining labor market impacts in destination or source countries. But there is more to high-skilled workers and their emigration than simple wage effects, and that is why we devote a whole chapter (chapter 5) to the topic.

High-skilled workers play a central role in today’s global economy. They are innovators, entrepreneurs, scientists, teachers, and role models for the next generations. They lead, coordinate, and manage activities of other high-skilled people in complex organizations. High-income destination countries depend on foreign talent to create and sustain many of their industries, including many that are at the forefront of knowledge creation. Low-income countries, which already suffer from human capital shortages, fear the impact of brain drain on their economic growth, public finances, and delivery of key services such as health care and education. It is not surprising that the global mobility of talent is a major policy concern entangling the gains from globalization as well as its pitfalls.

Over time, migration has become increasingly high skilled, presenting new challenges for both host and destination countries. In 1990, the first year for which we have comprehensive data, about 40 million labor market-age (above age 25) migrants resided in the 27 high-income OECD countries. Migrants with a primary education made up almost half of the total stock, and those with tertiary education accounted for about 27 percent. In 2010, labor-market-age migrants numbered over 85 million, with tertiary-educated migrants accounting for about 43 million—close to 50 percent of the total.

The rapid increase in high-skilled immigration is due to the increase in both the supply of tertiary-educated workers across the world and the demand in OECD countries. Figure O.17 presents the shares of the tertiary educated in the labor forces (blue bars) in OECD and non-OECD countries since 1990. The orange bars show the share of tertiary educated among the emigrants from the same regions to the OECD countries over the same time periods. The patterns in this figure lead to several observations. First, the share of tertiary educated among all emigrants moving to OECD countries has been nearly triple that of the education level of the underlying labor forces in each decade. High-skilled workers are simply far more mobile, as shown earlier. Second, the massive increase in high-skilled immigration is driven primarily by the increase in the number of the high skilled in the world population. Since 1990, the share of the high skilled increased more than 60 percent in non-OECD countries. Third, quite remarkably, both OECD and non-OECD origin countries send similar shares of high-skilled migrants to OECD destination countries—over 40 percent as of 2010—despite the fact that the share of tertiary-educated individuals is three to four times higher in OECD countries. Still, it is the non-OECD countries that experience particularly high rates of high-skilled emigration.

The rapid increase in the share of high-skilled migrants, the skill selection, presents itself at the country level as well. Figure O.18 plots the share of the tertiary educated among immigrants, emigrants, and native-born populations for 2010, the latest year of data. The horizontal axis of the left and right panels presents the emigrant and immigrant skill rates, respectively.

Education levels among the native born or non-migrants are on the left and right vertical axes. Observations below the dashed 45-degree line imply that emigrants (or immigrants) are more educated than the native-born workers. As can be seen, almost every country is below these lines, implying countries send and receive more educated migrants than they retain. Small and lower income countries are especially exposed to this disproportional emigration of skilled workers. Only in the case of a number of high-income countries—including the United States—is the average immigrant slightly less skilled than the average native worker: these countries lie above the 45-degree line on the right panel.

The extent of concentration emerges even more prominently in the case of high-skilled immigrants who are concentrated in a few destination countries. Figure O.19 presents the cumulative distribution of migrants by skill level. The graph implies that the top 10 destination countries account for 75 percent of the high-skilled immigrants in the world. Among these, four Anglo-Saxon destinations—Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States—are home to almost two-thirds of all high-skilled migrants. No such concentration exists among source countries.

Economic factors again explain much of this variation in emigration and immigration patterns. Countries with higher returns to education and higher income levels—in other words, high-income OECD countries—attract more-skilled migrants. As an economy rewards education, the composition of immigrant inflows responds by becoming more skilled. Meanwhile, high-skilled migrants can more easily overcome physical distances, linguistic differences, and policy barriers.

Immigrants play an outsized role in contributing to key high-skilled activities. They are disproportionately employed in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields, and as inventors and innovators. For example, migrants are responsible for about 10 percent of international patents filed under the Patent Cooperation Treaty. Looking across developed countries, figure O.20 shows that immigrants’ share among inventors is significantly higher than the overall share of immigrants in nearly every country. Furthermore, inventors from developing countries make up a relatively high share, especially in Canada and the United States.

Policies for high-skilled immigration

Across the globe, countries are increasingly adopting more skill-selective immigration policies that can typically be divided into two broad policy regimes. On one hand, demand-driven policies require that incoming migrants first acquire a job in the destination country. Migrants’ almost immediate employment is therefore prioritized, and potential employers and current labor market conditions play a key role in determining the sectoral and occupational composition of migrants. Supply-driven policies, on the other hand, require incoming migrants to be evaluated by a points based system. Preference is given to those who possess more desirable labor market characteristics such as younger age, higher education, experience, occupation, and language proficiency. In these regimes, migrants generally obtain employment permits without an actual job offer. The assumption is that they will find employment after their arrival.

The trouble with supply-driven immigration schemes is that—as repeatedly emphasized in this overview—there is little evidence on what type of immigrant most benefits a host country. Personal characteristics—including motivation, creativity, entrepreneurship, and industry-specific knowledge—are difficult to observe but are essential in determining the success of a migrant in the labor market. The best indicator for the contribution of a migrant to the economy of a host country is the evaluation given by the labor market: a job offer. To repeat our previous point once more: Governments should listen to the voice of labor markets in designing high-skilled immigration policies as well as general immigration policies. Demand- or employer-driven immigration programs, such as the U.S. H-1B, -H-2A, and H-2B visas, are preferable over supply- or immigrant-driven point systems that allow for immigration without a job offer.

The implication is not that different visa categories have no role but rather that governments should not try to micromanage work permits or try to guess which skills are more important. Instead, government policies should rely more on market mechanisms. If there are only a limited number of work permits available, the flexibility of an employer-driven scheme is preferable to a system based on hard-to-determine desirable immigrant characteristics. This is true for both high-skilled and low-skilled immigration schemes.

What about the impact on source countries?

Despite the issue’s importance and the attention it receives, the evidence on the impact of high-skilled emigration is, however, quite inconclusive. Data constraints—the empirical difficulty of identifying the effects of skill shortages on poverty, growth, or other economic indicators—contribute to the challenge of determining high-skilled emigration’s true costs or benefits. One solution is to combine global migration databases with macroeconomic models to simulate the impact of skill-biased emigration on poor countries. The results of this exercise are presented in figure O.21.

The critical determinant of the impact of high-skilled emigration is the extent of productivity spillover that the high skilled generate across the economy. If no such positive productivity spillovers exist, high-skilled emigration has a relatively small negative impact—about 1 percent—on income levels across the board (green line in figure O.21). In the presence of the spillovers, however, the impact can be quite severe—a decline of almost 6 percent—especially for those origin countries with per capita income levels below $3,000 (red line). Remittances sent back home (orange line) somewhat but not fully compensate for this loss.

One common response of origin countries is to restrict emigration, which brings up several important practical, economic objections to restricting emigration. First, all evidence suggests that high-skilled migrants might be less productive if prevented from migrating. Migrants—high and low skilled—experience huge income gains on migrating. A large part of what makes them productive is the work environment in the destination country. Without the potential income gains from migrating, it is unclear whether these migrants would have acquired these skills in the first place. Second, in practice, it is quite difficult to impose and enforce such mobility restrictions. The same way destination countries cannot seem to prevent entry, in the face of market forces, source countries cannot effectively prevent departure.

If governments cannot impede emigration, what should they do? Recent research highlights at least two promising ways to take advantage of the global market for high-skilled workers and ideas: First, source countries of high-skilled migrants should engage with their diasporas, and maximize their externalities. Second, they can encourage return migration.

Emigrants typically continue to be actively engaged—both socially and economically—with their home country. The most common economic engagement takes the form of remittances, which account for an important source of income for many families in developing countries. Diaspora engagement programs also attempt to connect investors and entrepreneurs abroad with investment opportunities at home, and foster the transfer of technology and knowledge from abroad. Promising evidence suggests that countries can successfully encourage the return of their high-skilled diaspora. The idea behind such programs is that it is valuable for people to emigrate and acquire skills abroad. Rather than preventing emigration, these programs seek to subsequently encourage the return of successful emigrants. An example of such a program is the Malaysian Returning Expert Program, which provides tax incentives to successful emigrants who return to Malaysia. The evidence suggests that the program is successful; it encourages more return migration and roughly pays for itself as the return migrants pay taxes (at, albeit, lower rates).

The simulations in the presence of such “brain gain” effects imply that such forces may compensate for the losses from high-skilled emigration and lead to overall economic gains (blue line in figure O.21). Nevertheless, we need to emphasize that the evidence on high-skilled emigration, its impact, and its implications are less than ideal. This is one area where new data and research are desperately and immediately needed.

International coordination of migration policy

The policy recommendations put forth in this overview are primarily described as unilateral policies, designed by the destination countries in most cases, with minimum input from or coordination with origin or other countries. The recommendations reflect the migration policies usually implemented independently by countries. However, we know from a wide range of areas such as international trade, finance, and security that many policies would greatly benefit from international cooperation. Unilateral policies, inherently, generate externalities on partner countries that can be internalized via cooperation and coordination.

Almost no multilateral frameworks exist for regulating economic migration. The main exception is very limited agreements concerning refugees. There are several important exceptions at the regional level, such as the regional labor mobility arrangements within the EU or East Asia. This lack of any multilateral design is in stark contrast to the international trade architecture or financial cooperation where international institutions (such as the World Trade Organization) have contributed to open borders, increase trade, coordinate monetary policies, and improve regulatory enforcement. The absence of formal and established cooperation and coordination between governments in the migration policy space leads to many inefficiencies, conflicts, and crises. Our last observation is that there is an obvious need for policy coordination—whether at the bilateral, regional, or multilateral level.

Final thoughts

The debate on the economics of migration needs both sides to be better listeners. Many economists, who believe in the virtue of open markets, are rightly focused on the efficiency gains that would be realized if labor were to move more freely. Despite the large range of estimates, the gains, especially those realized by the migrants, will be substantial—as evidenced by the wage gaps across markets. The mistake is to ignore the distributional impact and dislocation such flows would generate, especially in destination countries, as the efficiency gains are realized.

For those who oppose migration, the reverse is true. Their focus is on the distributional impacts of migration—mostly on migrants taking away jobs and lowering wages. They deny or ignore the significant efficiency gains—or the countless hundred dollar bills—that we are leaving on the sidewalk. Both sides have valid points, and both sides are looking for the solution in the wrong place.

The solutions—the policy measures—need to make the pie as large as possible and, at the same time, figure out a way to distribute it more equally. Such redistribution schemes need to include the winning and losing segments of the labor force not only in the destination countries but also in the source countries. This process requires coordination and forward thinking among policy makers. That is the only way we can establish political mechanisms to convert economic gains into reality. And, we need to add, these challenges are not unique to migration but apply to all other aspects of globalization—from trade to global warming to finance.

We are fully aware these are easy statements to make but daunting tasks to implement. We are hopeful that the analysis and the recommendations in this study will contribute to this process.

[※ World Bank. 2018. Moving for Prosperity: Global Migration and Labor Markets. Policy Research Report. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1281-1. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO

This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an official World Bank translation. The World Bank shall not be liable for any content or error in this translation.

This is an adaptation of an original work by The World Bank. Views and opinions expressed in the adaptation are the sole responsibility of the author or authors of the adaptation and are not endorsed by The World Bank.]

세계은행이 펴낸 정책보고서 「번영을 위한 이주 : 국제이주와 노동시장」 뒷표지

세계은행이 펴낸 정책보고서 「번영을 위한 이주 : 국제이주와 노동시장」 뒷표지

<pinepines@injurytime.kr>