세계은행이 펴낸 정책보고서 「번영을 위한 이주 : 국제이주와 노동시장」 표지

세계은행이 펴낸 정책보고서 「번영을 위한 이주 : 국제이주와 노동시장」 표지

이주의 장기적 영향 - 이민자 통합 및 동화

지금까지의 논의는 노동 시장에 대한 이민의 상대 임금 및 고용 영향과 가능한 정책 대응에 초점을 맞추었다. 이들은 대부분 정적 문제인 경향이 있다. 이제 우리는 장기적인 동적 문제로 눈을 돌린다.

이민의 장기적인 결과를 이해하는 데 중요한 것은 이민자들이 수용국에서 얼마나 잘 동화되는지의 문제이다. 모든 이민이 일시적인 것은 아니다. 영구 일자리에는 영구 이민자가 필요하다. 이것은 특히 직업이 훈련, 회사 또는 위치 특정 인적 자본 투자, 또는 장기적인 사회적 및 직업적 관계를 필요로 하는 경우이다. 이민자들은 목적지 국가의 언어, 관습, 직업 및 교육 요건을 숙달해야 한다. 저숙련, 고숙련 이민자를 막론하고 이민자의 궁극적인 성공과 전반적인 기여는 이민자와 고용주가 해당 지역의 특정 기술과 인적 자본에 투자하는 정도에 달려 있다.

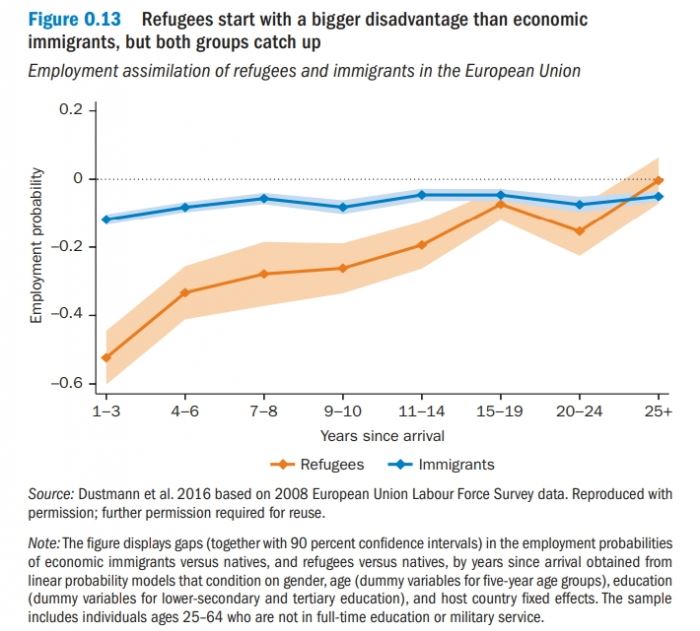

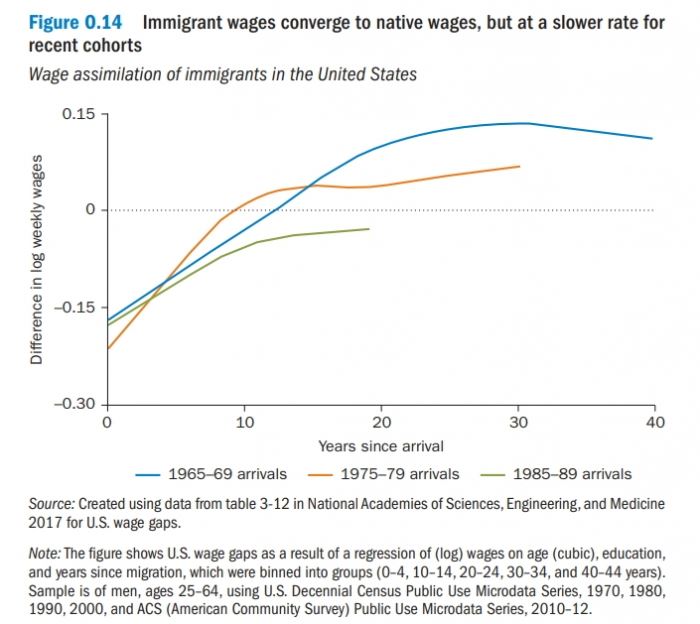

도착 당시 이민자와 난민은 평균적으로 원주민에 비해 고용, 임금, 직업의 질 면에서 심각한 경제적 불이익을 받고 있다. 그 후 이민자들은 임금과 고용 면에서 원주민과 동화되고 따라잡는다. 그림 O.13과 O.14는 도착 이후 몇 년 동안 동화 속도를 보여준다(유럽 연합 EU 고용의 경우 그림 O.13, 미국 임금의 경우 그림 O.14). EU에서 난민은 경제적 이민자보다 훨씬 낮은 초기 고용률로 시작하지만 이후 훨씬 더 빠른 증가를 경험한다. 미국에서 이민자 임금 동화 속도는 긍정적이지만 최근 이민자 집단의 경우 둔화되었다.

영속성을 위한 경로는 경제적 통합을 촉진할 수 있다

통합 및 노동 시장 동화 과정은 새로운 이민자에게 비용이 많이 들고 벅찬 일이다. 새로운 작업 환경에 적응하고, 새로운 사회 및 문화생활을 만들고, 언어 장벽을 극복하는 데는 시간, 노력 및 재정적 자원이 필요하다. 통합을 위해서는 이민자들이 문화-, 고용- 및 지역-특화 인적 자본을 투자를 해야 한다. 이 프로세스에는 언어 습득, 기술 교육 및 문화 통합이 포함되지만 이에 국한되지 않는다. 결정적으로, 이러한 투자는 이민자가 수용국에 체류하려는 기간에 따라 달라진다. 이민자들이 단기 체류를 원하는 경우, 그 수용국에 대한 노력과 기타 자원 투자를 꺼릴 수밖에 없다. 예를 들어, 많은 유럽 국가에서 도착 집단의 50%가 10년 이내에 목적지 국가를 떠난다.

특정 목적지 국가는 영구적인 경로를 제공하지 않음으로써 통합을 적극적으로 방해한다. 그 동기는 동화되지 않은 이민자들이 고용이 끝나면 떠날 가능성이 더 높기 때문이다. 그러나 이러한 정책 중 상당수는 목적지 국가에 사회적, 문화적, 경제적으로 피해를 줄 수 있다. 이주 노동자들은 그들이 얼마나 오래 머물 것인지에 대한 확신이 없기 때문에 자신의 직업에 완전히 능숙해지지 않는다. 문화적으로나 경제적으로 고립된 이민자 커뮤니티, 특히 젊은이들은 결국 더 큰 비용을 부담하게 된다. 이러한 문제는 근로자나 고용주의 장기적인 헌신과 특정 투자가 필요한 직업을 가진 이민자에게 특히 문제가 된다. 정책적 함의는 국가가 그러한 영구 직업을 얻는 이민자를 위해 영주권 또는 시민권을 취득할 수 있는 명확한 경로를 만드는 것을 고려해야 한다는 것이다.

이민자들은 가족과 함께 법적으로 안전하고 보호되는 거주 및 고용 권리를 가져야 한다. 불확실성은 비효율로 이어지며 목적지 국가의 이민자와 고용주 모두에게 더 큰 장기적 비용을 초래한다.

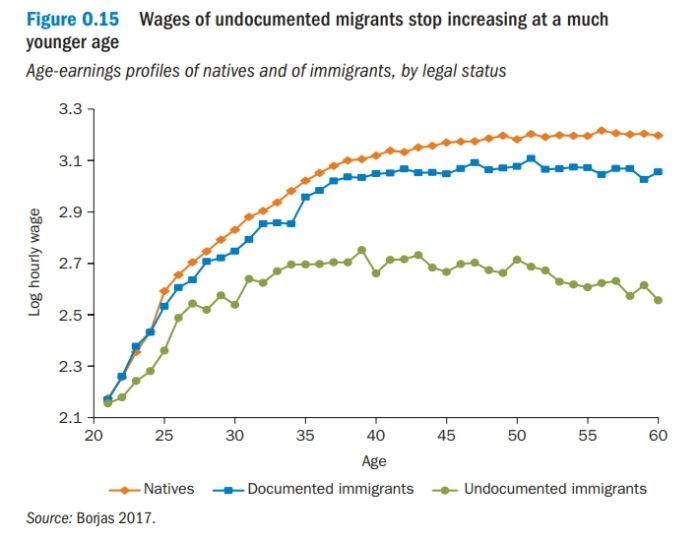

고용 관련 투자가 매우 높은 경향이 있기 때문에 거주 및 고용 안정성은 고도로 숙련된 근로자에게 특히 중요하다. 이를 충분히 인식하고 있는 많은 목적지 국가들은 고급 기술 이민자들에게 특권적인 법적 지위와 우선권을 부여한다. 대조적으로, 저숙련 또는 미등록 이민자들은 동화와 통합에 가장 큰 장벽에 직면해 있다. 서류미비 이민자와 많은 국가에서 난민은 공식 노동 시장에 참여하는 것이 금지되어 있으며 교육 및 의료혜택과 같은 공공 혜택에 대한 접근이 제한되어 있다. 수용국에 통합할 수 있는 능력이 심각하게 제한되어 있고 추방될 위험이 있어 수용국 고유의 문화 및 사회적 자본에 대한 투자를 더욱 위축시킨다. 그림 O.15는 미국에서 출생한 근로자와 합법 및 서류미비 이민자의 연령 소득 프로필을 보여준다. 놀랍게도, 서류미비 이민자들은 30세 이후에 거의 임금이 인상되지 않는 반면, 원주민 노동자와 서류 이민자들은 40대 이상에서도 수입이 증가한다.

특히 불행한 상황은 취업 허가를 발급하지 않는 나라에 있는 세계 난민의 거의 절반이 직면하고 있다. 노동권을 거부하는 것은 난민의 복지와 수용국에 해로울 수 있다. 난민이 비공식 노동 시장에 독점적으로 흡수되면서 경제적으로 가장 취약한 많은 토박이 노동자들과 경쟁하고 해를 끼친다. 저숙련 노동자, 특히 저숙련 여성 노동자는 비정규직일 가능성이 높기 때문에 노동시장 이탈과 난민 유입으로 인한 임금하락의 직격탄을 맞고 있다. 공식적으로 노동불능자는 정부 재정에 추가부담을 준다. 왜냐하면 세금수입의 손실에다 실직 원주민 노동자들에게 제공되어야 하는 더 높은 복지 혜택이 수반되기 때문이다. 따라서 목적지 국가는 노동 시장에 점진적으로 진입할 수 있도록 노동 허가 부여를 고려해야 한다. 취업 허가증 발급은 대부분의 목적지 국가에서 정치적으로 민감한 주제이지만 대화(검토 과제)의 일부가 되어야 한다. 난민을 위한 적절한 노동시장 투입 정책은 한마디로 가장 경제적으로 취약한 원주민, 난민, 그리고 수용국의 재정에 도움이 된다. 그리고 이 제안은 정부가 노동 시장과 싸우지 말고 노동 시장과 협력해야 한다는 우리의 이전 요점과 완전히 일치한다.

이민자 자녀에 대한 투자로 인한 높은 수익

이민자의 동화와 통합이 특히 중요한 분야는 교육이다. 이민자 학생들은 다양한 국가에서 학교 학생들의 많은 비중을 차지한다. 그림 O.16은 이민자 배경을 가진 15세 학생의 비율을 보여준다. 경제협력개발기구(OECD) 경제 전체에서 학생의 10%가 1세대 또는 2세대 이민자이다. 두바이는 70%로 가장 높은 점유율을 가지고 있다.

학교에서 적극적인 통합 정책이 시행되지 않을 때 이민자 아동과 수용 지역 사회는 모두 수많은 도전에 직면한다. 이민자 아이들은 현지 언어에 대한 지식이 제한적인 게 대부분이다. 그들은 종종 본토에서 태어난 아이들과는 종교와 민족이 다르며, 일부는 부모가 교육을 제대로 받지 못한 사람들이다. 기존 증거에 따르면 이민자 자녀가 있으면 학교 교육의 질이 낮아져 내국인과 이민자 모두에게 낮은 시험 점수와 높은 중퇴율이 나타나는 경우가 많다.

교육의 경우 기존 연구의 정책적 함의는 다소 단순하다. 정부는 이민자 자녀를 학교에 통합시키는 데 현재보다 더 많은 투자를 고려해야 한다. 이민자 자녀가 많은 학교에 대한 추가 투자는 이민자와 원주민 자녀 모두에게 이익이 된다. 그러한 교육 투자는 아마도 토박이 친구들에 대한 잠재적인 부정적인 영향을 완화하고 이민자 자녀들의 미래 사회 경제적 성공을 보장하는 가장 저렴한 방법일 것이다. 이 정책적 답변은 급격한 고령화와 노동력 감소로 고통받는 고소득 국가에서 특히 중요하다. 장기적으로 이러한 추가 투자는 스스로 보상받을 것이다. 단기적으로는 이미 논의된 바와 같이 이주 노동자로부터 걷는 세금으로 자금을 조달할 수 있다.

The long-term impact : Immigrant intergration and assimilation

The discussion so far has focused on the relative wage and employment impact of immigration on labor markets and possible policy responses. These tend to be mostly static issues. Now we turn to the long-term dynamic issues.

Crucial to understanding the longer-term consequences of immigration is the question of how well immigrants assimilate in their host country. Not all immigration can be temporary; permanent jobs require permanent immigrants. This is especially the case where the job requires training, firm- or location-specific human capital investments, or longterm social and professional relationships. Migrants will need to master the language, customs, and professional and educational requirements in the destination country. The eventual success and overall contributions of immigrants, low- and high-skilled alike, depend on the degree to which they and their employers invest in such location-specific skills and human capital.

At the time of their arrival, immigrants and refugees are, on average, at a severe economic disadvantage, as measured by employment, wages, and occupational quality, compared to natives. Subsequently, immigrants assimilate and catch up with natives in terms of wages and employment. Figures O.13 and O.14 illustrate the pace of assimilation—figure O.13 for employment in the European Union (EU) and figure O.14 for wages in the United States—by years since arrival. In the EU refugees start with much lower initial employment rates than economic immigrants but subsequently experience much more rapid increases. In the United States, the rate of immigrant wage assimilation is positive but has slowed for more recent immigrant cohorts.

A pathway to permanence can facilitate economic integration

The process of integration and labor market assimilation can be costly and daunting to new immigrants. Adapting to a new work environment, creating a new social and cultural life, and overcoming linguistic barriers take time, effort, and financial resources. Integration requires that immigrants make culture-, employment-, and location-specific human capital investments. This process includes, but is not limited to, language acquisition, technical training, and cultural integration. Crucially, these investments depend on the duration of the stay that an immigrant intends in a host country. If immigrants intend to stay only a short time, then they may be reluctant to devote effort and other resources to host country–specific investments. For example, in many European countries, 50 percent of an arrival cohort leave the destination country within 10 years.

Certain destination countries actively discourage integration by providing no pathway to permanence. The motivation is that nonassimilated migrants are more likely to leave once their employment is concluded. However, many of these policies may end up harming the destination countries socially, culturally, and economically. Migrant workers never become fully proficient in their occupations because they remain uncertain about how long they will stay. Culturally and economically insulated immigrant communities, especially their youth, end up posing larger costs in the long run. These issues become especially problematic for immigrants with jobs that require longer-term commitment and specific investments by workers or their employers. The policy implication is that countries should consider creating a clear path to permanent residency or even citizenship for migrants who obtain such permanent jobs.

Together with their families, immigrants should have legally secure and protected residency and employment rights. Uncertainty leads to inefficiency and to even greater long-term costs for both the migrants and their employers in the destination countries.

Residency and employment security are especially important for highskilled workers because their employment-specific investments tend to be very high. Fully aware of this, many destination countries give privileged legal status and priority to high-skilled immigrants. In contrast, lowskilled or undocumented immigrants face some of the greatest barriers to assimilation and integration. Undocumented immigrants and, in many countries, refugees are barred from participating in the formal labor market and enjoy only limited access to public benefits, such as education and health care. Their severely constrained ability to integrate in the host country and the risk of deportation further discourage their investment in host country–specific cultural and social capital. Figure O.15 depicts age-earnings profiles for native-born workers and for legal and undocumented immigrants in the United States. Strikingly, undocumented immigrants experience nearly no wage growth after age thirty, whereas native workers and documented immigrants experience earnings growth well into their forties.

A particularly unfortunate situation is faced by almost half of the world’s refugees who find themselves in a country that does not issue work permits to them. Denying the right to work can be detrimental to refugees’ welfare and to the host country. As the refugees are absorbed exclusively into informal labor markets, they compete with and harm many of the most economically vulnerable native-born workers. Low-skilled workers, especially women, are most likely to be informally employed and, thus, experience the brunt of the labor market displacement and wage declines due to refugee inflows. The inability to work formally places an additional burden on public finances because of the lost tax revenue or higher welfare benefits that need to be provided to the unemployed native-born workers. Hence, destination countries should consider granting work permits to allow gradual entry into their labor markets. Issuing work permits is a politically sensitive topic in most destination countries, but it should be a part of the dialogue. Appropriate labor market insertion policies for the refugees, in short, help the most economically vulnerable natives, the refugees, and the public finances of the host country. And this suggestion is fully consistent with our earlier point that governments should not fight labor markets but work with them.

High returns from investing in immigrant children

An area in which immigrant assimilation and integration is particularly important is education. Immigrant students represent a large fraction of school children in a range of countries. Figure O.16 shows the share of 15-year-old students who have an immigrant background. Across Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) economies, 10 percent of students are first- or second-generation immigrants. Dubai has the highest share, with 70 percent.

Both immigrant children and host communities face numerous challenges when active integration policies are not in place in schools. Immigrant children may have limited knowledge of the local language. They are often of different religion and ethnicity than native-born children, and some have parents who are themselves poorly educated. The existing evidence shows that the presence of immigrant children may lower the quality of school education, resulting in lower test scores and higher dropout rates for both natives and migrants.

The policy implication of the existing research in the case of education is rather simple. Governments should consider investing more heavily than they currently do in integrating immigrant children in schools. Additional investment in schools with many immigrant children benefits both immigrant and native-born children. Such educational investment is possibly the cheapest way to mitigate potential negative spillovers on native classmates and, of course, guarantee the future social and economic success of the immigrant children. This policy answer could be especially important in high-income countries suffering from rapid aging and shrinking labor forces. In the long term these additional investments will pay for themselves. In the short term they could possibly be financed by a tax on immigrant workers as already discussed.

[※ World Bank. 2018. Moving for Prosperity: Global Migration and Labor Markets. Policy Research Report. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-1281-1. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO

This translation was not created by The World Bank and should not be considered an official World Bank translation. The World Bank shall not be liable for any content or error in this translation.

This is an adaptation of an original work by The World Bank. Views and opinions expressed in the adaptation are the sole responsibility of the author or authors of the adaptation and are not endorsed by The World Bank.]

세계은행이 펴낸 정책보고서 「번영을 위한 이주 : 국제이주와 노동시장」 뒷표지

세계은행이 펴낸 정책보고서 「번영을 위한 이주 : 국제이주와 노동시장」 뒷표지

<pinepines@injurytime.kr>

저작권자 ⓒ 인저리타임, 무단 전재 및 재배포 금지